Grief, Rituals, and Why We Care About TV Finales

TV shows stay with us a long time, it's no wonder we feel so strongly when they end.

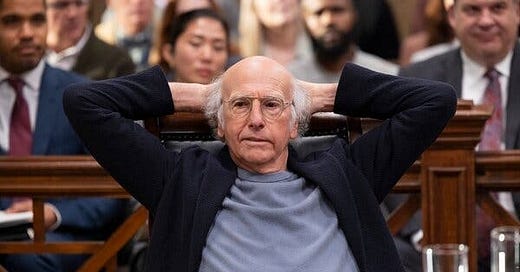

24 years ago, the very 1st episode of Curb Your Enthusiasm aired on HBO. The sitcom was created by Seinfeld co-creator Larry David and stars said co-creator playing a version of himself. Larry, now set for life from the success of Seinfeld, finds himself getting into constant petty disputes and strange social interactions as he has nothing better to do with his time. A show spanning well over 2 decades, it’s incredibly difficult to synopsize as the show was less about an overarching story, and more about the situations Larry finds himself in. With all the free time in the world, there was nothing too small for Larry David to complain about across the 12 season show as he pokes holes in the fabric of social etiquette and expectation.

On April 7th, 2024, the series finale to Curb Your Enthusiasm aired, officially ending the show after nearly a quarter of a century. This show first began in the year 2000, meaning it’s been around for the entirety of the 21st century. No matter what insane thing was going on in your personal life or in geopolitics, you always had the assurance that if you turned on your television, Curb was there. Now, Larry David has finally decided he’s said enough. I recently watched the series finale to Curb, a show that’s been on since I was barely 2 years old, and it made me think about one of the most discussed cultural touchstones: the TV series finale.

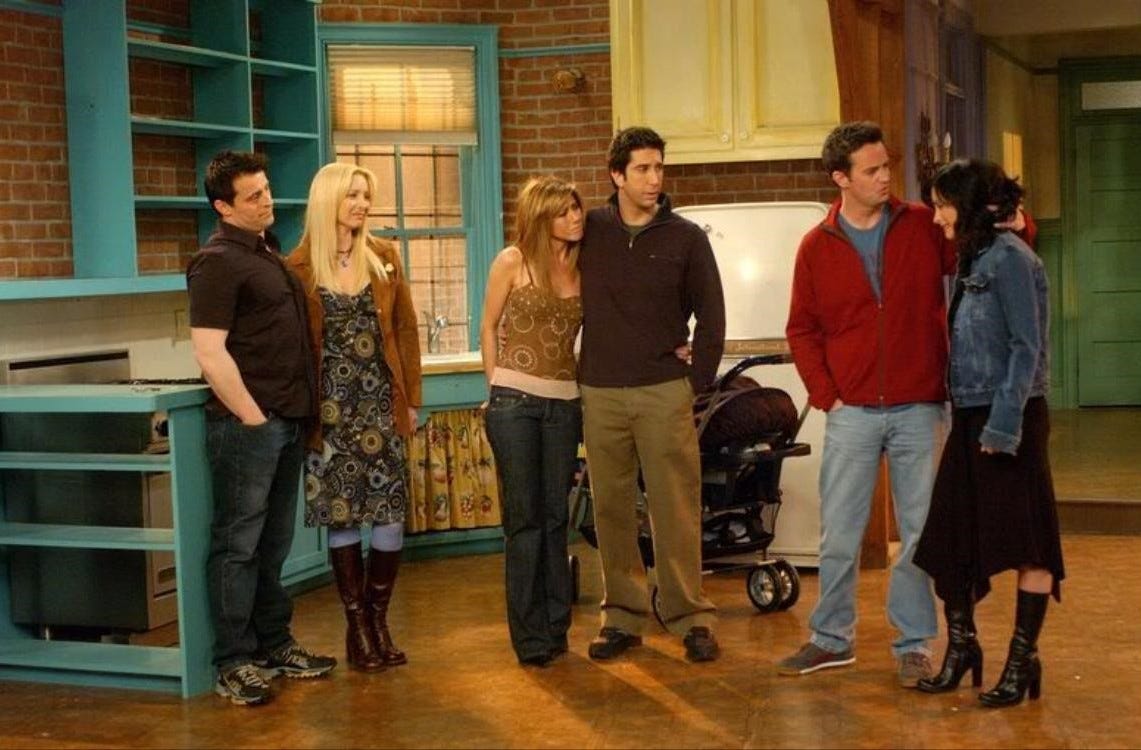

What does it mean to say goodbye to a work of fiction that’s been so regularly appearing in our lives that it never occurred to us that we might have to pull the plug one day? Historically, series finales are some of the most talked about and watched episodes a TV show will ever have. The series finales of Friends, Seinfeld, Cheers, M*A*S*H, and Family Ties, are all included on the top 10 most watched TV episodes of all time. A finale is also often one of the most controversial episodes of a series. Lost, Seinfeld, and most recently Game of Thrones are all major popular examples of a series finale that was hated when it aired, and still widely regarded negatively. It seems that no matter the show, a finale will always get people talking. Why do we care so much about finales, why do endings hold such unique importance?

To answer this question, I’m going to talk about grief. That universal experience we as people share due to the finite nature of existence, and the reality that we sometimes can’t bear to face: that all things do eventually come to an end. Grief is a feeling we experience when we have lost something, most commonly a loved one. This experience forces us to face both how vulnerable we are, and how easily and suddenly our entire world can fall into disarray. Judith Butler describes this in her book Precarious Life, saying:

“I think one is hit by waves, and that one starts out the day with an aim, a project, a plan, and finds oneself foiled. Something takes hold of you: where does it come from? What sense does it make? What claims us at such moments, such that we are not the masters of ourselves?”

To many this experience of grief most likely rings true. You start your day not planning to be unraveled, and then you are suddenly struck with a pang of sorrow. You randomly come across a picture, or you pass by an old restaurant you used to go to. The sights, sounds, and smells of the world have come to be associated with someone you loved, and now that someone is gone so every instance of experience, every memory, every stimulus comes with a sense of sadness.

To me, grief is proof that we as individuals are made up of more than just ourselves. We are defined by the world around us, and that includes the people in it. These important bonds we share with people are a part of our DNA, and so when we lose these important people we also lose something that made us us. Judith Butler describes this in Precarious Life as well, saying:

“It is not as if an ‘I’ exists independently over here and then simply loses a ‘you’ over there, especially if the attachment to ‘you’ is part of what composes who ‘I’ am. If I lose you, then I not only mourn the loss, but I become inscrutable to myself. Who ‘am’ I, without you?... On one level, I think I have lost ‘you’ only to discover that ‘I’ have gone missing as well.”

To lose someone is to also lose a part of yourself, and that means that you are forever changed whether you like it or not. To be alive is to change, it is to wake up every day a slightly different altered version of yourself because you have one more day of experience under your belt. Some days and experiences will define you in very miniscule and seemingly inconsequential ways. Other days might define your entire life, permanent adjustments to your soul and your psyche. Normally we undergo change very slowly over the course of many years, which is why death, loss, and sudden endings can come as such a shock as they force us to undergo change in such a short amount of time.

We as people are all our own individual Ships of Theseus, with pieces of us constantly being adjusted, replaced, or changed. This sense of change is fundamental to the experience of grief. As Judith Butler puts it:

“Perhaps, rather, one mourns when one accepts that by the loss one undergoes one will be changed, possibly forever. Perhaps mourning has to do with agreeing to undergo a transformation (perhaps one should say submitting to a transformation) the full result of which one cannot know in advance. There is losing, as we know, but there is also the transformative effect of loss, and this latter cannot be charted or planned.”

Judith Butler goes on to use this understanding of grief defined in Precarious Life to criticize American society’s pro-war tendencies particularly in the wake of the 9/11 attacks. I am going to use this understanding of grief to talk about TV shows. Let me cook.

In summary, Butler’s framework of grief is an emotion or experience one has when undergoing a change within oneself due to a loss in life that one cannot control, cannot be prepared for, and/or cannot predict in what ways one will be changed as an outcome from these events. Grief is the feeling of being forced to change against one's will. A change that we didn’t sign up for, and when we look out at the light at the end of the tunnel of mourning, we cannot know what will be waiting for us there.

If we accept this understanding of grief to be true, then this feeling can be applied to more than just major losses such as the death of a loved one. While this is the most intense, and arguably the largest grief one might ever go through, grief can and will come to us all in smaller or more medium sized doses. A breakup or divorce with a partner can also be defined as an experience that causes grief. Moving away at a young age and having to say goodbye to all your friends at school as you’re then forced to make new ones in a new place is a form of grief. Your favorite restaurant you used to eat at closing down is a form of grief. The significance of these various griefs may vary, but they are all defined by the common variable of losing something, and you having little to no say in that thing being lost.

These things that you once had, whether they be people, places, or daily activities, all defined who you were and how you acted. They were a part of your daily or weekly rituals, incorporated into your schedule. Now that they are gone, your behaviors must change. If I used to text my best friend every day, and now whether due to death or a personal falling out that friend is absent from my life and we no longer maintain contact with one another, this is a fundamental change to the way I move through the world and thus myself. This change within ourselves and our actions, is the core of grief.

The things that can cause us grief also tend to stay with us for a long time. Friends, loved ones, restaurants, schools, homes, etc. are typically expected to be in our lives for many years. By being with us for so long, they embed themselves into our daily habits and rituals. This means that as we slowly grow and develop in minute ways day by day, we often have the anchor of a close friend or family member that can maintain familiarity like a lighthouse in a fog of change. Our connections to the people and things around us take time to be planted and take even more time to grow into the intimate and weighty things that we will look back on fondly and with melancholy once they are gone.

In this way, I think TV shows can be a breeding ground for grief. The structure of television is such that it is the art form that stays with us the longest in order to fully experience it. A movie is typically watched from start to end in one sitting, typically in a time span that lasts 1-3 hours. Most people will look at a painting in a museum for a few minutes to an hour. A song or album can be listened to quickly and constantly. Books, while often taking significantly longer than these other examples, still typically are completed in a shorter period of time than most television shows. Avid book readers very regularly complete a full reading within a few days or weeks, a month or two at most.

Most traditional television shows differ in that they are released episodically, meaning you have to wait a week between each episode. If a show has a 10 episode season and is released weekly, it is going to take you 2 and a half months to complete that season, which is already longer than any of the examples I just mentioned above. Even if a full season of a show is released all at once, there is still the waiting period between seasons as one waits for a show’s creators to write and film a new chapter in the story until its eventual end. This waiting period can sometimes be at least a year, if not longer. This is to say that if a show has multiple seasons, it will be in your life for a very long time. Going back to the example of Curb Your Enthusiasm, if you started the show when it first aired and watched it as it was released, that means that the show has been in your life for 25 years. That’s a relationship you have with a television show that’s longer than most modern marriages in the United States.

Even if you’re retroactively watching a show that has been completed for a while now (e.g. many people doing their first watch of Sex and the City right now since it came to Netflix), it still might take you a much longer time to complete it compared to most other art forms. Unlike reading, which is determined by the speed at which you can read, it’s not very practical to make a show happen faster. If each episode is an hour, then you’re going to have to sit there for the full hour each time. For most of us who have jobs, lives, and responsibilities, that means that we can only watch a few episodes per viewing session. It’s very likely that it will take someone at least a few months to complete a show that has 5+ seasons (which is the majority of most popular television shows of the past that one would most likely watch).

In a nutshell, watching TV shows takes a very long time, and often the only way to complete such a monumental task is to integrate the show into our lives through a habit. Perhaps you watch 1-2 episodes every night at 7pm after finishing up all your tasks for the day. Maybe you get together with your friends each week on a Sunday night. Regardless of how you split up the time, the reality is that it is going to take time.

This leads to the phenomenon that occurs when people finish their favorite television shows, the post-series depression. It is very common for people to commit to watching a series, and then upon finishing the series to have this feeling of “what the hell do I do with my life now?” There’s even an entire wikihow article on how to deal with your favorite show ending. Some even put off watching their favorite show’s finale, citing this feeling of never wanting the show to end.

It is this precise feeling that I’m arguing is grief. The feeling of your favorite show ending, and your life feeling somewhat aimless after, is an instance of grief and mourning. It might not be as big or affecting as the loss of a loved one (at least I would hope not), but it is grief nonetheless based on this understanding that grief is the process of undergoing change that is out of your control.

You can’t control whether or not your favorite show ends, that is up to the creators and the studios funding the show. Once you finish the show, the way the show was embedded into your life is now gone. You no longer watch an episode or 2 of Friends every night after 7pm, and you don’t get together with a group on Sundays to watch the most recent episode of The Last of Us. These things you used to do in your life, that defined you in some way, are now gone because the show is finished.

It is this combination of how long it takes to complete a TV show and the loss of the daily/weekly viewing rituals once the show is completed, that makes television a common place for “fun-sized” experiences of grief, particularly when everyone is discussing the show’s finale. Over the course of a very long time while watching a show, these characters on screen become your friends in a way. The same way I might Facetime someone I know every Thursday, I might also see Larry David every Sunday at 8/7 central. Once the show ends, like when someone you loved is gone, you never get to see them again.

When Matthew Perry, who played Chandler on Friends, passed away recently, my Aunt described her reaction by saying “it felt like one of my friends died.” She, along with my parents and other members of my family, immigrated to America in the 1990’s. Friends was of course a hit at the time, and was a defining part of their first experiences in this country. Ross, Chandler, Monica, Rachel, Joey, and Phoebe kept my family company as they established roots in a new country, giving them life updates in 23 minute spurts each week. What could be more apt, then calling these on screen characters your friends? What else could you feel but grief at the news that one of them passed away, or at the experience of watching the series finale in real time in 2004? I’ve noticed this pattern in many immigrants who have come to America, with many of them citing whatever American sitcom was on at the time of their arrival being a sort of comfort show. My parents still rewatch and reference Friends on a regular basis.

This isn’t to say that a grief similar to post-series depression can’t be experienced in other art forms. I myself have most definitely felt grief while watching a movie or reading a book. It’s more to say that it isn’t surprising that the art form that takes up so much actual time in our lives when we watch it also tends to leave so many upset and sentimental when it’s over. The other best examples I can think of where pieces of media evoke grief and such intense controversial discussion culturally, are film or book franchises/series (e.g. when Harry Potter ended). This is because when a different medium such as films and books take on the franchise/series format, they are adopting the television style of storytelling, with each film/book in the series representing an “episode” of an ongoing story that will take many years of real human time to get through as we live our lives.

In this way, a series finale is like a funeral. It is our opportunity as viewers to eulogize, memorialize, and say goodbye to this thing that we love, and pay our respects. A series finale is a viewer’s way of getting closure, and viewers need closure, otherwise the grief might never be stifled. This is why a bad series finale can leave so many viewers upset, as they never get that proper send off. Hence the intense reactions when a series finale is not up to par.

I think this feeling of grief is also echoed in a common question I hear asked all the time on the internet: What is a piece of media you wish you could experience for the first time again? I’ve seen friends and strangers alike answer this question with great passion and sense of nostalgia, discussing a show, movie, video game, or album that forever changed them. When it comes to television specifically, I also notice it’s very common to rewatch your favorite show over and over again as you pine for this experience to be recurring, thus making the show a “comfort show.” Many of my friends have told me how they’ve watched The Office at least 6 times. This yearning for the memory of your first experience with a show, and the decision to watch it again and again, reads in a way as looking through a scrapbook of old photos and remembering the thing you once had in your life now gone. It’s no wonder that so many people also clamor for remakes, reboots, and sequel shows to their favorite series so that they never have to say goodbye. Avatar: The Last Airbender is a great example of this, with a live action remake that was recently released, multiple new shows greenlit, and a film that will continue the story of the original series with our protagonists as adults announced. Sometimes it’s easier to live in a state of stubborn refusal to say goodbye than to acknowledge that something is over.

Recently, I took to social media and asked people to vote on which they prefer when it comes to a TV show’s rollout: the 1 episode weekly release or the Netflix/streaming style of dropping the entire season at once to binge. The results were 60% in favor of the 1 episode a week style, with the remaining 40% split evenly across preferring the binge style or having no preference at all. This reflects the general sentiment I’ve seen online for years now, which is a nostalgia for the days when most shows were released weekly rather than all at once. With this framework of understanding that finishing a beloved show can elicit grief, it’s not surprising to see that people are so much more in favor of the weekly release. If you love something, you want it to be in your life for a while. You wouldn’t want all of your experiences with a loved one to occur in one weekend, only to say goodbye forever come Monday morning. In this same way, if you love a show you most likely want it and its characters to stay by your side. An exciting event you look forward to consistently like seeing a friend for dinner every weekend.

Art, like all things we love, is something we never want to say goodbye to. It’s something that we would much prefer to have embedded in our lives consistently for as long as we can. No matter how hard we try, nothing we love gets to stay with us forever. We will always feel some sense of melancholy and mourning when that time together comes to an end. What’s important is that we appreciate the time we spend with that thing that we love, whether it be a person, a place, or a TV show.