Are All Writers the Same These Days? If So, Why?

There’s an epidemic of personal essays and writers migrating to Substack that all sound the same, why is that?

If you’re reading this or anything else I’ve written for this newsletter, it means you have some semblance of an understanding of the platform Substack. If this is true, it also means there’s a chance that my newsletter is not the only Substack you’ve read, with many new writers starting their newsletters in recent years. As an avid reader with your ear to the ground, you may have heard that there’s been a widely documented and criticized boom of a form of writing known as the personal essay, an often harrowing first person account detailing a personal experience a writer has decided to divulge to readers. This upwards tick in the popularity of personal essays and the advent of new Substack writers has coalesced into an issue people are taking to task: everyone’s writing sounds the same now.

Particularly in the last year or so, it’s become a cliche to write on Substack, or to call yourself a writer while mostly using this platform to post lists of what you’ve been reading or the albums you’ve been listening to. I myself am somewhat guilty of both of these things. While I’m hoping to mostly populate this newsletter with critical essays and seriously improve my writing, my last post before this one was an update post, and my existence on this platform at all is in part due to me finally joining the Substack hype at the beginning of this year. It seems many people are interested in becoming writers, dissecting culture, or talking about their personal experiences online in a more formal way, or at the very least sending out an email blast letting everyone know how much they like the new Clairo album. This criticism of the uptick in Substack writers is one that is particularly pointed at women. It seems that the “girl essay,” or women on the platform who want to dissect womanhood and online culture, has become a trend with its own formulas/clichés.

I’m not the first person to write about this for Substack. Emily Sundberg wrote a piece earlier this month for this platform detailing how everyone is writing in the same way and how the floor for what counts as “being a writer” is being lowered into “lifestyle inspo” content and media recommendations. Eliza McLamb wrote a piece titled “Everyone’s Writing Sounds the Same Now (and that’s fine)” arguing that while the Substack writer industrial complex is real, it’s also just another iteration of a very normal phenomenon where writers and artists improve their craft by first copying what they see. It takes a while to develop a distinct voice, and often what you see already working and trending is an easy way to get started.

I’m not here to take either of these stances criticizing or accepting this issue to task. I would highly recommend reading both of the pieces linked above, they’re very good and well thought out. I’m more interested in explaining why this might seem more prominent than in years past. Why do all these writers suddenly sound the same? Why does it seem like a lot of the writing on this platform and elsewhere isn’t very good, and why is there so much of it in a way that maybe we haven’t seen before?

Surprise surprise, it’s because of the internet. Everyone writes the same because of Substack trends and what we see other people write. Everyone dresses the same because of fast fashion and Pinterest boards. Everyone listens to and makes the same music because of what goes viral on TikTok. The list goes on. The internet has made it exceedingly difficult for niche, siloed communities with discernible individualism to exist for long before getting co-opted or commodified for the masses to mimic. The conditions for a unique unclouded perspective are harder to cultivate when every day a person hops online and sees the same things as millions of others, the opinions of those millions of others, and is now pressured to maintain some level of agreement with those opinions. All of this is brought to you by the algorithms these social media platforms operate on, a mirrored feed for all of us online.

So the internet may have exacerbated the issue, but Eliza’s point still stands. Even if this is the case, artists and writers borrow inspiration from others all the time. Stealing is often the mechanism by which we are able to improve to the point that we no longer have to steal and can actually just “take inspiration from.” Early on in your creative learning journey, you will often end up doing what is borderline plagiarism as you find the line between homage and copying. As she says in her essay:

“The first-ever works of any artist are usually no spectacular feat of ingenuity. And I’m not talking about a debut album or novel here. I mean the first time some kid ever picks up a guitar it’s probably going to sound like if Pink Floyd got blended up and put through a washing machine. Go ahead and look back at your old poems from middle school (I know my audience, I know you have them). They probably have a line or two stolen from Sylvia Plath or a Tumblr text post. They’re probably very bad but also earnest and clearly trying to be good. This is how anyone learns at all. It is a good thing for art and ideas to remain, in most circumstances, public goods available to take and make use of and create more things… Most of the failures here are simply natural parts of any young writer’s process and they should be allowed and even encouraged to happen.”

I think what’s new about the Substack writer industrial complex is not that writers and artists are all sounding the same in their creative infancy, as Eliza rightly states this is a very normal thing that happens. It’s that for many readers and audiences they’re actually seeing that mimicry happen for the first time, and this is what I think the internet has done that’s actually distinct. Before the internet, there wasn’t a platform where anyone could post their early, cringey, and derivative creative work for audiences to see before being fully developed. If you wanted to seriously make it in a creative field, you had to prove your worth to the established canon of artists and general people in the industry who had already made it.

To better illustrate this point, I’ll use myself as an example. Behind the scenes of this Substack newsletter, I’m a freelance writer and journalist who every single week is incessantly emailing, pitching, and submitting writing to editors, newspapers, magazines, and publications. The overwhelming majority of these pitches and submissions are either ignored or outright rejected. Even when I do get a piece published, there is a rigorous process where I send a draft over to an editor for edits. Sometimes there are multiple passes/back and forths before the final version of the piece gets published. While this process certainly makes it harder to get your work out there in the first place, it also means that there’s a certain level of quality that writing has to meet before the public lays eyes on it.

This of course is not a 100% foolproof process. Sometimes a magazine lets something through that isn’t quite great, and sometimes an editor might pass on a good idea for budgetary or other reasons. At the minimum though, this eliminates a lot of the fluff and forces you as a writer to truly take your own work to task and reflect on it. Is this thing I’m pitching good? What are the common edits I’m noticing I get from editors when I’m working on a piece? I myself have looked back on many of my old pitches in my email archive with a sigh of relief that they were declined. In hindsight, I can clearly see that many of these pitches were either not a good idea or were derivative, and the thought of having potentially thousands of readers of an established publication read my early, shallow, or cringey work makes me feel like I dodged a bullet.

Recently I pitched something to an editor, who ended up passing on the pitch but gave the reason that while it was a good idea, the magazine had already extensively published a lot of other writing on the topic. This is exactly where the internet’s existence comes into play and creates the friction of the Substack writer industrial complex. In earlier times, I would have to take this rejection from the editor and leave it at that. Maybe I would end up writing the piece anyway, but crucially it would only be for myself in a journal or diary setting where no one else would see it. Now with the internet, I could easily say “this editor was wrong” and then write the thing anyway for a public forum such as this Substack, meaning that dozens, hundreds, thousands, potentially millions of eyes could read it depending on how viral it could go.

There’s a chance that this would be a worthwhile endeavor, after all maybe that topic had only been extensively written about in that one magazine, and that there’s a different audience who would benefit from my slightly distinct perspective on the subject. There’s a strong chance however, that the editor’s instincts were right, and that if I were to self-publish that piece, it would end up being a rehash of things most people have already written or read. Ultimately leading to derivative and trite work that instead of being written for my own personal eyes specifically for improvement, would end up being email blasted out to readers unnecessarily.

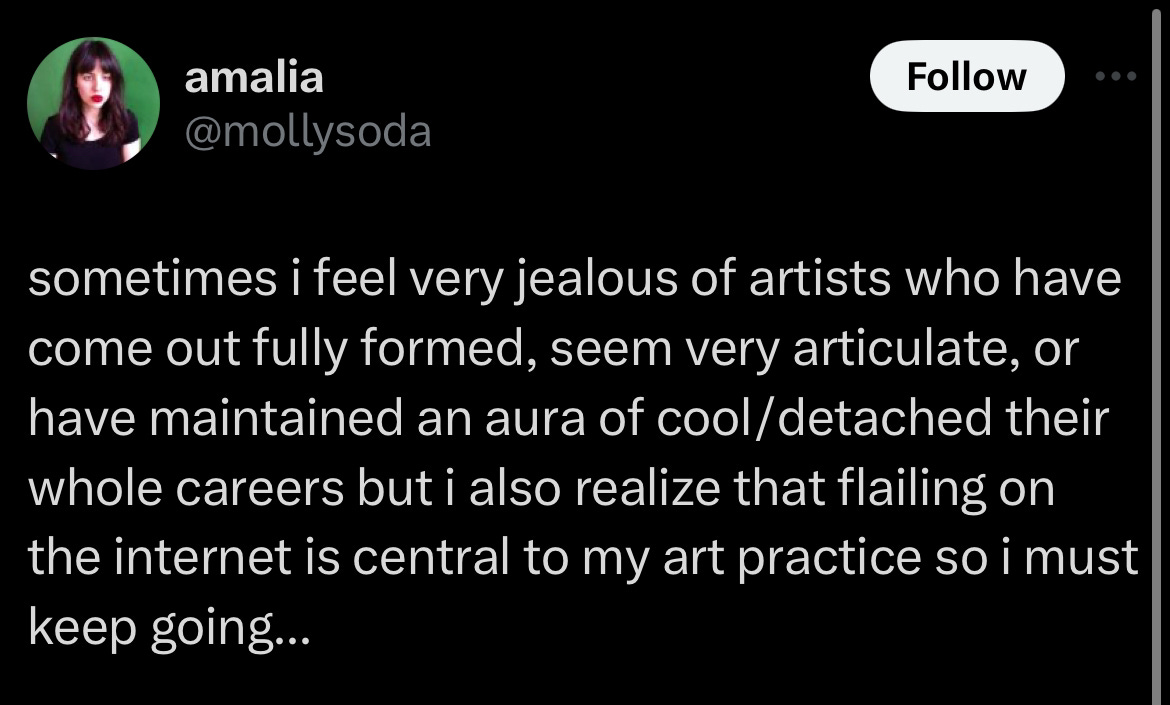

This is the double edged sword of platforms like Substack, and the general public forum that is social media and the internet. On one hand, more artists and creatives than ever before have the opportunity to nurture their artistic ideas online and take non-traditional paths to breaking into the industry and finding success. This allows for more diversity in creative spaces and for historically marginalized voices (women, BIPOC, etc.) to find opportunities previously unattainable due to discrimination and the limited number of openings in traditional industry settings. On the other hand, this means that the “puberty stage” of most artist’s creative journeys is now on public display in ways that previously happened behind closed doors, causing audiences to have to actually experience more of the misses before getting to the hits. This is the territory that both artists and their audience find themselves in online, and this extends to more than just writers. Musicians, filmmakers, video essayists, and more all have the same issue of having their rough drafts as well as their later final drafts be public in ways that were previously uncommon before the internet.

The main worry is that a lot of these online platforms (Substack included) also give you the opportunity to monetize and profit off of what is otherwise mediocre or shallow work, which may lessen the motivation or incentive to improve at all. Posting a rough draft online and achieving virality might make you mistake it for a final draft. “If it ain’t broke don’t fix it” so the saying goes, but on the internet a more accurate description might be “if it’s broke but gets you money and views, don’t fix it either.” I’d still like to believe though that most of the writers and artists on online platforms such as this one do genuinely want to improve rather than just make a quick buck, and that this period of derivative work en masse that many are disparaging is just some growing pains. Perhaps it’s naive, or just me projecting my own personal goals on others, but I think that this thought comes with a hopeful prospect for those despairing at the quality of writing on Substack right now: it will eventually get better!

Many of these writers and artists will eventually improve and find their unique voice, no longer simply replicating or rehashing the words they’ve read from other publications. Substack and other sites like it are a relatively new platform, and many of the writers and readers that have migrated over have only done so in the last 3-4 years. It might take some time, but a lot of us will develop and hone our craft as right now we are in the early stages of our budding newsletters, and I’m confident that I’m not the only one with a hunger to continue evolving.

I think as readers we can certainly give these writers some grace as they go through their artistic puberty. Their work isn’t perfect, but they’re working on it, and knowing that we’re simply reading their WIPs right now can be a helpful context for why it might not always succeed at what it’s attempting. However I still think criticisms of these trends are important. It’s good to keep things on the right track, and make sure that the systems that are rewarding a lack of depth in the work don’t win, and the only way to do that is to point out when things are becoming unoriginal or cliché. These criticisms also prove that no matter what the algorithms and viral trends say, there is still an appetite that audiences have for creative and artistic work that has depth, nuance, and a distinct voice with a unique perspective.

As artists and writers, I think it’s important to remind ourselves that it’s okay for our work to be “in progress” and that finding what makes you unique is a lifelong process! We improve and change for the entirety of our lives, and that should be exciting. There’s no such thing as perfect, but it’s always good to grow! While it’s a helpful tool early on to just copy what others do, don’t give into the temptation to just mindlessly mimic the work of others forever, even if that aesthetic or style seems to be “trendy.” It’s important to figure out what you actually want to do, and what you value. Artistic journeys eventually do blossom, they just take awhile sometimes. I myself am on one of those journeys, and who knows, maybe in a few years from now I’ll look back on this Substack and many of the essays I wrote for it and think something to the tune of “what the hell was I thinking?”